The CrowdStrike cyber incident brought retail, transportation, banking, and more to a shocking standstill. In the aftermath, what can insurers do to gain clarity on the true exposures in their books before the next Blue Screen of Death?

You may have noticed that a global IT outage occurred on Friday 19 July 2024, making CrowdStrike, a security technology provider, into a household name, sending Microsoft scrambling to release recovery tools and advice as users faced the dreaded ‘Blue Screen of Death’.

The cyber incident was attributed to a software update from CrowdStrike for its Falcon EDR product that caused problems with PCs, servers and IT equipment running Microsoft Windows, triggering substantial disruption across many businesses.

The CrowdStrike outage is the latest high-profile disruptive cyber event to have left underwriters fearing unforeseen correlations within their portfolios, and questioning scenarios for cyber aggregation risk.

The event mimicked a supply chain incident, according to Damini Mago, associate director of product management for cyber at Moody’s, causing cascading and widespread disruptions among interconnected systems.

“Unlike a malicious attack, due to the vendor’s trusted position within the networks of affected enterprises, this update event could skip the initial access hurdle and many other kill chain steps, and avoid protective, defensive measures designed to thwart threat actors,” she said.

“Early reporting states the update triggered a system-level problem, resulting in the affected Windows operating system computers entering into a dreaded ‘Blue Screen of Death’ loop. The machines would reboot, encounter the Blue Screen of Death, and then restart – endlessly,” Mago added.

Who got hit?

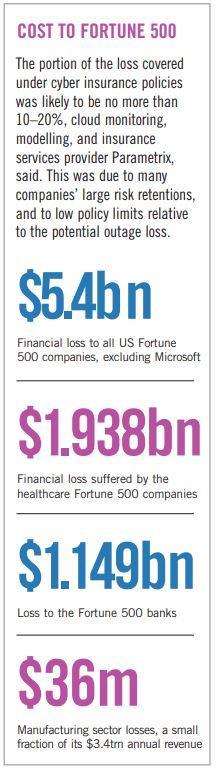

According to tech firm Parametrix (see box) a quarter of US Fortune 500 firms were impacted, including every airline and 43% of retailer and wholesaler firms. About three quarters of health and banking sector firms suffered direct costs.

Beyond such primary financial losses, CrowdStrike’s impact on critical services resulted in a cascade of operational delays affecting the Fortune 500 companies and their downstream entities, Parametrix said.

With CrowdStrike’s estimated 20% market share for cyber security among large companies, and 50% of Fortune 500 companies, the flagship victims are household names, observes Tancred Lucy, vice president, Acrisure Re.

The number of companies that rely on a business using CrowdStrike Falcon in conjunction with Microsoft, is estimated to be in the millions, meaning insurers will need to plan to manage and address these exposures.

“This event is likely to be felt most acutely in the large and mid-market corporate space,” he says. “However, when considering that over 20,000 companies use CrowdStrike Falcon in conjunction with Microsoft, and many managed security service providers license CrowdStrike for their clients, it brings single point of failures and systemic exposures amongst SMEs into greater focus.”

How are insurers impacted?

CyberCube provided a preliminary estimate of insured losses between $400m and $1.5bn for the standalone cyber insurance market, adding to the Parametrix estimate (see box).

Meanwhile, Verisk’s Property Claim Services (PCS), has designated the CrowdStrike outage as a cyber catastrophe loss event.

“Which means it’s likely to exceed $250m industry wide insured loss,” says Tom Johansmeyer, global head of index classes, Price Forbes Re, and former head of PCS, speaking on a recent episode of The Political Risk Podcast.

“So, is it a cat? Yes. Is it carnage? No,” Johansmeyer says. “My back of the napkin on this puts it at probably $300-500m…I think on the worst possible days, it could approach $1bn, but that’s it.”

Acrisure has said that the expected wave of notifications following the event would mean losses under business interruption (BI) and dependent business interruption (DBI) insuring clauses.

A note from Moody’s said: “Most losses from the outage will be BI, which is a primary contributor to losses from cyber incidents. Because these losses were not caused by a cyber-attack, claims will be made under ‘systems failure’ coverage, which is becoming standard coverage within cyber insurance policies.”

Most cyber policies include triggers for malicious and non-malicious events, and BI and DBI coverage typically extends to incidents at IT vendors. Some cyber policies will also contemplate DBI coverage for non-IT vendors, while in this case. Further uncertainty arises from the many products, with different BI triggers, based on net loss of revenues or profits, for example, as well as potentially different limits within the same policy for BI, DBI and contingent BI claims.

Cyber insurance is still maturing. It has evolved in the past decade, from a third party liability product – focused on data privacy and the risk of breach – to more of a first party BI protection, expanded into contingent coverage, in parallel with the society-wide trend to the cloud.

That trend means most insureds, regardless of sector, have become reliant on outsourced third party cloud providers for core IT functions. This has contributed to a worrying lack of clarity among cyber underwriters about their true cyber exposures, suggests Dan Carr, head of cyber, Ariel Re.

“By moving infrastructure out of a business there is less visibility over those assets, and less operational governance as to whether those systems are available or not, and ultimately, the market has assumed that risk and uncertainty,” says Carr.

“The flow of exposure understanding and probabilistic judgment over those systems remains limited. Is that external system going to go down or not? In reality, at present, the market doesn’t know what the complete end-to-end risk picture looks like. Why is the market in this position? Clients have a clear need for this cover, but risk is being insured that we can’t fully and discretely articulate,” he continues.

“If you put this into another domain - such as natural perils - it’s not saying, ‘there is uncertainty around the frequency or the severity of an event’. In this instance, all the locations of the risk being insured, their health, and how they are managed is unknown. Long-term, that isn’t a sustainable means of providing insurance coverage,” Carr adds.

Feeling exposed?

The size of the cyber insurance industry has certainly grown exponentially in recent years. The global cyber insurance market reached $14bn last year, and is estimated by reinsurer Munich Re to increase to $29bn by 2027. For a rundown of the top 20 US cyber insurers, check out the table accompanying this article, published by Moody’s.

But is the industry overcooking the scale of cyber catastrophe risk? Johansmeyer certainly thinks so. “The insurance and reinsurance industry so thoroughly misunderstands cyber catastrophe risk, and it’s manifested in pricing, capital availability, risk transfer behaviour,” he says.

“There are some really good things being done from a weak understanding, and that’s what I’d like to see fixed,” Johansmeyer says. “You’ve got fears of cyber mega catastrophe that are unjustified; you’ve got fears of cyber war that defy both empirical evidence and state incentive structures; some of our fears as an industry make no sense.”

He adds: “The worst cyber-attack on critical infrastructure in history is generally believed to be the 2015 Russian attack against the Ukrainian power grid. This is the one everybody talks about. 230,000 people lost power for one to six hours. That’s the worst of it.”

Reinsurers have been among those most alarmed by cyber cat, including recent cyber war exclusions, highlighting an aversion to high aggregate exposures reaching systemic risk levels.

However, from a reinsurance perspective, supply is exceeding demand for cyber risk in 2024, sources agree, with clients buying less of the proportional products reinsurers have offered, retaining more risk.

This is leading some reinsurers to pursue aggregate stop loss and cat risk products that work on a per occurrence basis. However, buyers of cyber reinsurance have shown modest appetite for buying cyber cat products.

Ariel Re is among those reinsurers looking to grow in this area. Ariel Re typically reinsures malicious cyber events, Carr says, the basis for its cyber cat appetite, and therefore has limited exposure to a non-malicious systems outage event like CrowdStrike.

However, he sees CrowdStrike as an event likely to highlight uncertainty about exposures on insurers’ balance sheets, as underwriters struggle to answer such questions to board level, which may drive interest in buying cyber cat reinsurance covers.

“I don’t think CrowdStrike is a huge market loss, but nor is it going to breed confidence in Cyber’s scope of coverage, so I think investors and insurers are going to have some reconsideration of risk appetites” he says.

“If you’re writing significant aggregate limit on this basis, are you going to want to double your capital position in those circumstances? It’s unlikely, unless there is further development in coverage scope, exposure visibility, or reinsurance protections,” Carr adds.

While many reinsurers have moved to limit their own exposures, there is still little clarity about how big a “worst case” cyber cat event might turn out to be. Industry attempts to quantify cyber catastrophe risk are somewhat spotty at best. In 2023, the Lloyd’s market undertook a systemic risk scenario that it said revealed the global economy was exposed to as much as $3.5trn from a major cyber-attack, some $1.1trn of which was judged to come from the US market.

Johansmeyer says: “Swiss Re’s estimate that cyber insurance is 10% penetrated worldwide…would mean a $40bn industrywide insured loss would be $400bn economic loss addressable. But if you add up the 10% market share, that means the addressable insurance market is $4trn relative to global GDP of around $120trn last I saw.”

He continues: “Which means that $400bn economic loss to drive a $40bn insured loss is really going to be several times that, because you’re going to have economic losses that fall outside the addressable insurance market. You’re looking at something north of $1.5trn in economic loss to drive that $40bn insured loss.”

Johansmeyer’s PhD research has focused on building a history of cyber cat economic losses, as far back as 1998, arriving at an overall loss figure estimate for these cyber cats over the period.

“Adjusted for inflation at 3% you’re looking at $300bn [economic loss]. Are we going to see a single event five times 25 years of cyber cat losses? No, we’ve got to get real,” he adds.

No comments yet