A $41m High Court case points to PV’s soft market traits, despite the volatile geopolitical risk landscape, writes David Benyon, editor of GR.

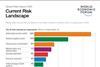

The growing political violence (PV) insurance market is understandably a focus for specialty re/insurance business, given the current, unstable geopolitical era that is spawning conflicts, tensions and crises across the globe.

PV, as it has become known, is typically underwritten on a direct and facultative (D&F) basis, relying on local carriers to front business, much of it passing to global specialty markets, such as Lloyd’s and the London market and regional speicalty re/insurance hubs, such as Dubai for Middle East and North Africa, Singapore for Southeast Asia, and Miami for Latin America.

This is a market that has grown with the geopolitical risk climate – particularly civil unrest in recent years – strikes, riots and civil commotion (SRCC) in underwriters’ nomenclature – and non-marine war risk, back in demand amid so many conflicts and tensions.

In June this year, what could be a landmark PV legal case reached the High Court of the UK. A judge decided in favour of a panel of re/insurers, after a disputed claim that began with the chaos of the Taliban’s seizure of power and US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

This case concerned two PV reinsurance policies, with around a dozen facultative reinsurers on a panel led by Hamilton and using market standard Beazley PV wording, issued by the claimant reinsurers and protecting a warehouse, part of Bagram airbase in Afghanistan.

The warehouse was owned by Anham, a private contractor, and was used to distribute foodstuffs and other provisions for the US military. The building stretched to 1.5 million square feet. After the Americans departed in summer 2021, the Taliban took possession, along with the rest of the country, ending the 20-years-long Afghan War.

Anham had bought insurance for the asset with Afghan Global Insurance, which took no active part in court proceedings, having transferred 100% of the PV risk to the panel of reinsurers on a fac basis, with Tysers as broker.

Why is this case important?

“It is an important decision for the London market because it is the first ever reported decision on a post 9/11 PV insurance policy, and also because it establishes an important precedent regarding the interpretation of one of the PV insurance market’s standard wordings,” said Andrew Tobin, partner, Mills & Reeve, the legal firm that successfully represented Hamilton in the Anham case.

“Specifically, the judgment settles the meaning of both loss and seizure in this particular wording,” Tobin added, discussing the details of the case in a webinar, available online, here.

Reinsurers sought summary judgment on two related grounds:

The first was that the reinsurance wording excluded any loss directly or indirectly caused by “seizure”, and that it was common ground that the loss of the warehouse was caused by its seizure by the Taliban. “Anham’s response was that “seizure” under the exclusion must be by “a governing authority”, which didn’t extend to the Taliban,” Mills & Reeve said.

The second was that the reinsurance only covered property damage and not deprivation loss consequent upon the seizure. “Anham disputed that, saying that on a true construction of the reinsurances there was cover for deprivation loss. Anham said the property was lost, akin to the theft of property,” the law firm added in its summary of the case.

On ground one, the court found that the meaning of “seizure” was answered by settled authority. It means “all acts of taking forcible possession either by a lawful authority or by overpowering force”. On ground two, the court found that the wording covers only “political violence risks and consequent property damage, not political risks and consequent deprivation loss.”

The judge for the case made this point in his written judgment: “I consider that the reinsurances afford cover in respect of political violence risks and consequent property damage, not political risks and consequent deprivation loss.”

Political risk and Political violence

The Anham case represents an important dividing line between two separate types of products that exist in the re/insurance world to transfer geopolitical risks that can look somewhat similar to the layman, or possibly even the insurance buyer.

PV is often grouped with war and terrorism, focused primarily on physical damage to property.

Political risk, on the other hand, is usually grouped with trade credit insurance, and is focused on recovering financial losses that can arise from government expropriation of physical or financial assets.

Both of these lines of business involve closely watching interrelated geopolitical risks. Political risk is the more expensive product, and more complicated to place, whereas the PV market is more crowded, competitive and – despite the risk landscape – awash with capacity on the table.

It is telling that the Anham case involved a political risk claim under a PV policy. While add-ons can lead to overlaps between lines of business, given the competitive pricing and soft terms on display in the PV market, it is unlikely such a scenario would emerge the other way around.

The differences between PV and political risk are something that brokers need to explain to clients to avoid claims litigation, while PV underwriters would benefit from reviewing and tightening their wordings with the same aim in mind.

The D&F market for PV risk has had an eventful past five years, with a slew of big high profile conflicts and civil unrest events, such as mass protests and rioting in Chile and South Africa, war losses related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and steep rises in the cost of reinsurance since that conflict began, including the Russia, Ukraine, Belarus (‘Rub’) exclusion that has led some D&F carriers to underwrite more war or PV risks net, retaining risk, raising the stakes for them.

Pricing is at different levels between D&F and treaty reinsurance. President and CEO of IGI, Waleed Jabsheh, spoke to GR in Monte Carlo at this year’s RVS reinsurance rendezvous. IGI underwrites some PV on a D&F basis, but Jabsheh was more interested in the PV market’s potential as a treaty reinsurer, citing treaty rates since Russia’s 2022 invasion as more adequate than pricing in the D&F market, one link down the risk transfer chain.

“PV is a lot more attractive to us as reinsurance rather than as a direct play,” he told GR, back in September. “When the PV reinsurance market took significant action, two years ago, to correct the nature of how it was underwritten, after Ukraine and South African riots, you would have hoped that the action taken would filter through the direct market; some of it did, but nowhere near the extent that I would have expected.”

You might think that with the world facing an age of insecurity – a year of elections and global civil unrest fears, multiple hot wars, cold wars, proxy wars, hybrid wars and trade wars in play – the risk environment would have elevated pricing for PV.

Not so, because capacity on the table from re/insurers in this space is more than meeting demand, keeping pricing soft and competitive. PV is best described as a buyer’s market, something which puts stress on individual underwriters to show some discipline, while D&F brokers are understandably keen to deliver savings for clients, and/or include as much as they can for the price of that policy.

“Because of the capacity available in the market, you can buy pretty much whatever you’re looking for. Policy forms are broadened. As the market softens, you see the policies being offered wrapping around all risk forms,” said Dan Callow, lead underwriter for political violence, terrorism and war lines of business at specialty insurer and reinsurer IQUW.

“You get all the additional sub-limits that you would get in your property policy as well, which gives a broad amount of coverage to clients. And the limits you can buy for things like war on land are pretty enormous in the market. I would definitely still classify it as a buyer’s market,” Callow added, speaking on a recent episode of The Political Risk Podcast, hosted by your correspondent.

Dodging bullets

The soft market for PV has somehow avoided systemic or globally market-turning losses in 2024. This is despite the heightened volatility in the underlying risk environment, with an unpredictable new era of ‘poly-crises’, lurching from one geopolitical shock to another.

This year was heralded as a “super year” for elections, meaning PV watchers’ attentions were largely on SRCC,.culminating with the 5 November US election victory of President Donald Trump.

Most US SRCC exposures still reside in the property all-risks market, rather than standalone PV policies. The biggest civil unrest insured loss in recent history – the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 – reportedly cost insurers more than $1bn, but did not fundamentally change commercial market buying behaviours.

If a big SRCC event were to hit the US under the incoming Trump administration, it would likely hit property insurers hardest. This could lead to an advantageous situation for PV underwriters able to do new business and underwrite newly excluded and highly priced SRCC risks new to the market within standalone policies, as has been the case after previous exclusions and shifts in buying behaviours following mass protests in Chile and South Africa.

In any case, elections-triggered mass SRCC events have, it seems, not come to pass in 2024. Donald Trump dodged a sniper’s bullet and two separate assassination attempts during this summer’s campaigning, which may have spared politically polarised tensions resulting into widespread PV.

Then, another metaphorical PV bullet was dodged for the market as a result of Trump’s decisive victory in the November election also avoided he scenario of a too-close-to-call and therefore disputed result, keeping a lid on domestic SRCC tensions – for now at least.

Internationally, the lid on war or PV tensions is shaking as steam rises from the boiling pot. This is where the youngish PV market is perhaps more vulnerable, with its traditional client type – large western multinationals operating in Global South countries – closely watching a maelstrom of geopolitical risk activity as the world enters 2025.

There is much talk of Trump’s shock election win affecting the war in Ukraine, possibly freezing that conflict in the short or medium term. However, this is subject to too many uncertainties to presume peace in Europe is just around the corner.

Regardless of what happens in Europe, events in the Middle East are still developing at great speed, and in ways that the best analysts or risk modellers could not have predicted just weeks ago.

Syria may not be a market with much in the way of insured assets after a decade of civil war, but the consequences of the recent regime change will be region-wide, and they are closely related to Israel and Iran’s ongoing region-wide conflict.

Callow warned: “Going back to the soft market and the amount of capacity that’s available, if you look at what the PV market has deployed as total limit across the Middle East, it’s an eye watering amount, and relative to the income it generates, it’s quite scary.”

In Asia Pacific, a cold war and a trade war between the US and China are adding to fears that China might invade Taiwan between now and the end of the decade, all combining to keep underwriters, analysts and perhaps most of us feeling on edge in 2025.

As another underwriter said, speaking anonymously about the risk of war between the US and China over Taiwan: “We’re talking about the unthinkable.”

No comments yet